November

23, 2012, 6:00 am - New York Times

Health Insurance Exchanges May Be Too Small to

Succeed

By DANA P. GOLDMAN, MICHAEL CHERNEW and ANUPAM

JENA

Dana P.

Goldman is the director of the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy

and Economics at the University of Southern California. Michael

Chernew and Anupam

Jena are professors of health care policy at Harvard University.

With the re-election of President Obama, the Affordable Care Act is back on

track for being carried out in 2014. Central to its success will be the creation

of health-insurance exchanges in each state. Beneficiaries will be able to go a

Web site and shop for health insurance, with the government subsidizing the

premiums of those whose qualify. By encouraging competition among insurers in an

open marketplace, the health care law aims to wring some savings out of the

insurance industry to keep premiums affordable.

Certainly, it is hard to be against competition. Economic theory is clear

about its indispensable benefits. But not all health care markets are composed

of rational, well-informed buyers and sellers engaged in commerce. Some have a

limited number of service providers; in others, patients are not well informed

about the services they are buying; and in still others, the quality of the

service offerings vary from provider to provider. So the question is: What

effect does insurer competition have in a marketplace with so many

imperfections?

The evidence is mixed, but some of it points to a counterintuitive result:

more competition among insurers may lead to higher reimbursements and health

care spending, particularly when the provider market - physicians, hospitals,

pharmaceuticals and medical device suppliers - is not very competitive.

In imperfect health care markets, competition can be counterproductive. The

larger an insurer's share of the market, the more aggressively it can negotiate

prices with providers, hospitals and drug manufacturers. Smaller hospitals and

provider groups, known as "price takers" by economists, either accept the big

insurer's reimbursement rates or forgo the opportunity to offer competing

services. The monopsony

power of a single or a few large insurers can thus lead to lower prices. For

example, Glenn Melnick and Vivian Wu have

shown that hospital prices in markets with the most powerful insurers are 12

percent lower than in more competitive insurance markets.

So health insurance exchanges are probably welcome news for hospitals,

physicians, and pharmaceutical and medical device companies throughout the

United States. If health insurance exchanges divide up the market among many

insurers, thereby diluting their power, reimbursement rates may actually

increase, which could lead to higher premiums for consumers.

Ultimately, economic theory predicts that the effect of insurance exchanges

on insurance premiums will depend on two offsetting factors. On one hand,

smaller, less-consolidated insurance companies may have less bargaining power

with large hospitals, physician groups and pharmaceutical companies, which

traditionally command substantial market power. Reimbursements to these parties,

as well as costs to insurers, may rise in a fractionated market, and if so,

these costs would be passed on to consumers as higher premiums. On the other

hand, exchanges may inject competition into the marketplace, reducing premiums

as even the smallest insurer can market its plans, forcing larger insurers to

lower their premiums to remain competitive. Which theoretical effect will

dominate in reality is an open empirical question with important policy

implications.

There is some evidence on how insurer market power affects premiums. Leemore

Dafny, Mark Duggan, and Subramaniam Ramanarayanan have

found that greater concentration resulting from an insurance merger is

associated with a modest increase in premiums - suggesting that concentration

may not help consumers so much - although they did report a reduction in

physician earnings on average. Over all, however, the evidence

is limited and mixed.

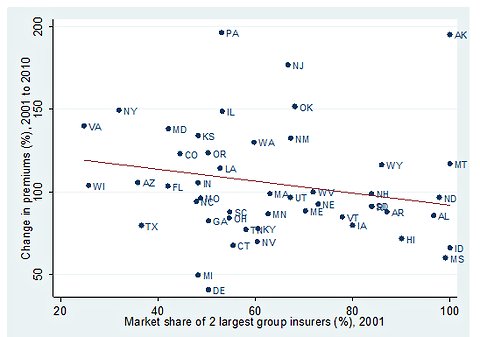

A simple analysis of the nationwide growth in premiums over the last decade

is illustrative. Using 2001-10 data from the National Association of Insurance

Commissioners, we examined the relationship between insurer market power

(defined as the market share of the two largest companies) and changes in

premiums. We found that concentration of insurer power -- hence less competition

- was not significantly associated with higher premiums, as can be seen in the

chart below.

Hawaii is a good example. Kaiser Permanente and Blue Cross Blue Shield

together controlled more than 90 percent of the insurance market in 2001. In

this highly concentrated market, the average premium rose only 72 percent over

the decade, compared to an overall increase of 135 percent nationwide. By

contrast, Virginia had one of the most competitive markets in 2001, with its two

largest insurers controlling only 25 percent of the market, yet premiums in the

state increased nearly 140 percent over the period.

Greater competition in the insurance industry -- either through health

insurance exchanges or other measures -- may not lower insurance premiums.

Weakening insurers' bargaining power could instead translate into higher costs

for all of us in the form of higher premiums.

In financial markets, we ask if banks are too big to fail. When it comes to

health care, perhaps we should ask if insurers are too small to

succeed.

Copyright 2012 The New

York Times Company